The phrase “Remember that you have promised to remind him, in the most tender manner, of his failings and to aid in his reformation as well as to vindicate his character when wrongfully traduced” represents one of the most profound obligations within Freemasonry, encapsulating the essence of what it means to be a true brother in the craft. This sacred duty, woven into the very fabric of Masonic obligation, speaks to a higher calling that transcends mere social fellowship and enters the realm of spiritual responsibility for one’s fellow man.

The Masonic Foundation of Fraternal Correction

Within the ancient landmarks of Freemasonry, this principle finds its clearest expression in the concept of brotherly love, relief, and truth—the three great pillars upon which the institution stands. The obligation to correct a brother “in the most tender manner” is not merely a suggestion but a solemn vow taken before the Great Architect of the Universe, binding the Mason to act as both guardian and guide to his brethren.

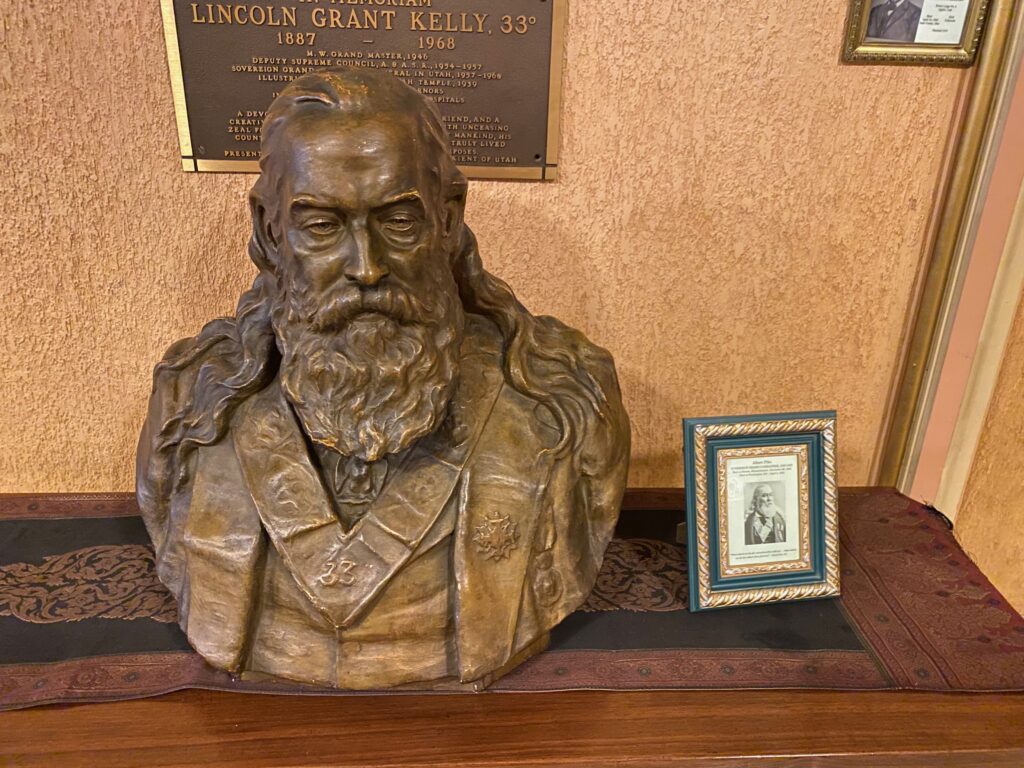

Albert Pike, in his seminal work “Morals and Dogma,” emphasizes that the Mason must be “ever ready to assist a distressed worthy Master Mason, his widow and orphans,” but this assistance extends beyond material aid to encompass moral and spiritual guidance. The Scottish Rite degrees, particularly the 14th Degree of Perfect Elf, elaborate on this concept by teaching that correction without malice, administered with love and understanding, is among the highest forms of service one can render to another human being.

The ancient charges of Freemasonry, dating back to the medieval stonemasons’ guilds, consistently emphasize the duty of mutual correction and support. The Regius Manuscript of 1390 speaks of masons who must “love well together as sisters and brothers,” implying not just affection but active concern for one another’s moral welfare. This tradition continued through Anderson’s Constitutions of 1723, which explicitly state that Masons should “act as becomes moral and wise men.”

Eastern Religious Perspectives: The Art of Compassionate Correction

The Eastern religious traditions offer profound insights into the practice of gentle correction that align remarkably with Masonic principles. In Buddhism, the concept of “Right Speech” as part of the Noble Eightfold Path encompasses not only avoiding harmful speech but actively engaging in discourse that promotes the spiritual welfare of others. The Buddha himself, in the Vinaya texts, established elaborate protocols for the correction of monks that emphasize privacy, gentleness, and genuine concern for the individual’s spiritual progress.

The Buddhist notion of “skillful means” (upaya) is particularly relevant here. This principle teaches that the method of correction must be tailored to the individual’s capacity for understanding and their current spiritual state. A harsh rebuke might cause one person to reform, while gentle guidance might be necessary for another. This mirrors the Masonic emphasis on correction delivered “in the most tender manner”—recognizing that the goal is reformation, not humiliation.

In Hinduism, the concept of “satsang”—association with the virtuous—inherently includes the duty of mutual correction and elevation. The Bhagavad Gita speaks of the wise person who, like a friend, shows others their faults not out of malice but out of love. Krishna’s correction of Arjuna throughout the great dialogue exemplifies this principle: firm in moral truth yet delivered with infinite compassion and understanding.

The Jain tradition, with its emphasis on ahimsa (non-violence), extends this principle to include violence of speech and thought. The practice of correcting others must be undertaken with such care that no unnecessary pain is inflicted, and the primary motivation must always be the spiritual benefit of the one being corrected. This aligns perfectly with the Masonic obligation to aid in a brother’s reformation while preserving his dignity.

Western Religious Traditions: The Christian Foundation

The Judeo-Christian tradition provides perhaps the most direct parallels to this Masonic obligation. Christ’s teaching in Matthew 18:15-17 establishes a clear protocol for fraternal correction: “If your brother sins against you, go and tell him his fault, between you and him alone. If he listens to you, you have gained your brother.” This passage emphasizes privacy, gentleness, and the ultimate goal of reconciliation—principles that directly mirror the Masonic approach.

Saint Paul’s letters are replete with instructions on the proper manner of correction within the Christian community. In Galatians 6:1, he writes, “Brothers, if anyone is caught in any transgression, you who are spiritual should restore him in a spirit of gentleness. Keep watch on yourself, lest you too be tempted.” This warning against self-righteousness is crucial to understanding the Masonic obligation—the corrector must approach his task with humility and self-awareness.

The monastic traditions of Christianity developed sophisticated approaches to fraternal correction that bear striking similarities to Masonic practice. The Rule of Saint Benedict, written in the 6th century, establishes procedures for correction that emphasize privacy, graduated responses, and always the hope of reformation. The abbot is instructed to “hate the faults but love the brothers,” a sentiment that perfectly captures the spirit of the Masonic obligation.

Thomas Aquinas, in his Summa Theologiae, addresses the duty of fraternal correction as an act of charity—not optional kindness, but obligatory love. He argues that just as we would save a brother from physical danger, so must we act to save him from moral peril. However, Aquinas emphasizes that this correction must be undertaken with prudence, considering the likelihood of success and the potential for causing greater harm through inappropriate intervention.

Philosophical Foundations: The Ethics of Moral Intervention

The philosophical implications of this Masonic obligation touch upon fundamental questions of moral responsibility and the nature of human relationships. Aristotle’s concept of friendship in the Nicomachean Ethics provides crucial insight here. He distinguishes between friendships of utility, pleasure, and virtue, arguing that only the latter involves genuine concern for the friend’s moral character. True friendship, according to Aristotle, requires the courage to speak difficult truths in love.

Immanuel Kant’s categorical imperative offers another lens through which to examine this obligation. If we universalize the maxim of gentle fraternal correction, we arrive at a world where all individuals take responsibility for the moral development of their fellows—a world that seems far preferable to one where moral indifference reigns. Kant’s emphasis on treating persons as ends in themselves, never merely as means, requires that correction be undertaken for the benefit of the corrected, not for the satisfaction of the corrector.

The Stoic philosophers, particularly Epictetus and Marcus Aurelius, emphasized the interconnectedness of human beings and the responsibility this creates for mutual care. Marcus Aurelius writes in his Meditations, “We were born to work together like feet, hands, and eyes, like the two rows of teeth, upper and lower.” This organic view of human society suggests that correction of others is not interference but necessary maintenance of the social body.

John Stuart Mill’s harm principle, articulated in “On Liberty,” might initially seem to argue against unsolicited moral intervention. However, Mill himself recognized that the boundaries between self-regarding and other-regarding actions are often unclear, and that genuine friendship creates special obligations that transcend general principles of non-interference.

The Vindication of Character: Justice and Mercy United

The second part of the Masonic obligation—”to vindicate his character when wrongfully traduced”—represents the complementary duty of defense. This obligation recognizes that in a world where reputation can be destroyed by rumor and slander, the brotherhood must serve as a bulwark protecting the innocent from false accusation.

This principle finds expression in the Jewish concept of “lashon hara” (evil speech), which forbids not only speaking ill of others but also listening to such speech when it serves no constructive purpose. The obligation to defend a brother’s character requires active resistance to gossip and calumny, positioning the Mason as a guardian of truth in a world often dominated by prejudice and false witness.

The Islamic tradition’s emphasis on “husn al-zann” (good opinion) requires believers to assume the best of others unless proven otherwise. This principle, when combined with the duty to defend the innocent, creates a powerful framework for protecting reputation and character. The Quran explicitly states that those who “launch a charge against chaste women” without proper evidence are to be rejected as witnesses, emphasizing the serious nature of character assassination.

From a philosophical standpoint, this obligation to vindicate character reflects a deep understanding of human dignity and the social nature of identity. Charles Taylor’s work on recognition suggests that our sense of self is fundamentally shaped by how others see us. Therefore, the duty to protect a brother’s reputation is really a duty to protect his very identity and capacity for moral agency.

The Tender Manner: Methodology of Moral Guidance

The specification that correction must be delivered “in the most tender manner” reveals a sophisticated understanding of human psychology and moral development. This requirement recognizes that the method of correction is as important as the correction itself—that a truth delivered harshly may be rejected, while the same truth offered with love may transform a life.

The ancient Greek concept of “parrhesia”—fearless speech or speaking truth to power—evolved throughout classical antiquity to emphasize not just courage in speaking truth, but wisdom in how that truth is communicated. Plutarch, in his essay “How to Tell a Flatterer from a Friend,” argues that true friends must have the courage to speak painful truths, but must do so with such evident love and concern that the bitter medicine of correction is made palatable.

Buddhist meditation practices offer practical techniques for developing the mental states necessary for tender correction. The cultivation of loving-kindness (metta) and compassion (karuna) prepares the mind to approach others’ faults without anger or superiority. The practice of mindfulness ensures that correction arises from wisdom rather than emotional reactivity.

The Christian mystic tradition speaks of the “spiritual direction” relationship, where a more experienced practitioner guides another in their spiritual development. The great masters of this tradition—from John of the Cross to Teresa of Avila—emphasize that effective guidance requires not only knowledge but love, patience, and the ability to meet each soul where they are in their journey.

The Modern Application: Relevance in Contemporary Society

In our contemporary world, marked by increasing polarization and the decline of traditional community structures, the Masonic obligation to gentle correction and character defense takes on renewed urgency. Social media and digital communication have created new possibilities for both constructive guidance and destructive gossip, making the Mason’s role as guardian of truth and protector of reputation more crucial than ever.

The psychological research on effective behavior change supports the wisdom embedded in this ancient obligation. Studies consistently show that correction delivered with empathy and respect is more likely to be accepted and acted upon than correction delivered with hostility or condescension. The work of psychologists like Carl Rogers on unconditional positive regard demonstrates that people are most open to change when they feel truly accepted and valued.

The concept of “restorative justice,” increasingly adopted in criminal justice systems worldwide, reflects principles that align closely with the Masonic approach to correction. Rather than focusing purely on punishment, restorative justice seeks to heal relationships and restore community harmony—goals that mirror the Mason’s obligation to aid in reformation while maintaining brotherly bonds.

The Universal Brotherhood: Implications Beyond the Lodge

While this obligation is specific to Masonic brothers, its principles have universal application. The recognition that all human beings are works in progress, deserving of both guidance and protection, forms the foundation of a more compassionate society. The Mason who practices these principles within the lodge becomes an agent of positive change in the broader community.

The philosopher Emmanuel Levinas spoke of the infinite responsibility we bear for the “Other”—a responsibility that includes both the duty to guide and the duty to protect. This responsibility is not based on contracts or agreements but on the fundamental recognition of shared humanity. The Masonic obligation formalizes this universal human duty within the specific context of fraternal relationship.

Martin Buber’s distinction between “I-Thou” and “I-It” relationships provides another framework for understanding this obligation. Genuine correction can only occur within an I-Thou relationship, where the corrector recognizes the full personhood and dignity of the one being corrected. This requires moving beyond mere rule-following to authentic encounter and care.

Conclusion: The Transformative Power of Sacred Obligation

The Masonic obligation to remind a brother of his failings in the most tender manner and to vindicate his character when wrongfully accused represents far more than a simple rule of conduct. It embodies a vision of human relationship that acknowledges both our mutual responsibility for one another’s moral development and our capacity for transformation through love.

This obligation challenges the modern individualistic assumption that we bear no responsibility for others’ choices or character. Instead, it asserts that true brotherhood—whether Masonic or universal—requires the courage to speak difficult truths and the commitment to defend the innocent. It recognizes that human beings are not isolated monads but interconnected souls whose wellbeing is intimately linked.

The wisdom embedded in this simple phrase draws upon the deepest insights of human civilization, from the Buddha’s teachings on right speech to Christ’s instructions on fraternal correction, from Aristotle’s analysis of friendship to Kant’s categorical imperative. It represents a convergence of religious and philosophical traditions around the fundamental truth that love sometimes requires difficult conversations and always requires faithful defense.

For the modern Mason, this obligation serves as a daily reminder that the principles learned in the lodge must be lived in the world. It calls us to be neither harsh judges nor silent enablers, but wise counselors and faithful defenders of truth and character. In a world increasingly marked by moral relativism and social fragmentation, the Mason who honors this obligation becomes a beacon of stability and hope—a reminder that human beings can indeed be their brothers’ keepers without becoming their brothers’ tyrants.

The transformative power of this obligation lies not merely in its effect on those who receive correction or defense, but on those who give it. The practice of gentle correction cultivates humility, wisdom, and compassion. The commitment to defend character develops courage, justice, and loyalty. Together, they form the Mason into the kind of person who makes the world a better place simply by being in it.

In the end, this ancient Masonic obligation points toward a vision of human community that transcends the boundaries of lodge or nation—a community where truth is spoken in love, where character is protected from false attack, and where each person takes responsibility for the moral wellbeing of all. It is a vision worthy of the Great Architect of the Universe and achievable by those who commit themselves to its practice with sincerity and dedication.

The phrase thus stands not merely as an obligation but as an invitation—an invitation to participate in the sacred work of human transformation and to contribute to the building of that more perfect union of souls that is the ultimate aim of all genuine spiritual endeavor. In remembering this promise, the Mason remembers not just a rule but a calling, not just a duty but a privilege, not just an obligation but an opportunity to serve the highest and best in human nature.